Spoiler alert! As the title suggests, I’ll be discussing the conclusion of Michael Schur’s wonderful The Good Place below. Proceed with an appropriate level of caution.

The iconic title card above, so simple and understated, gave way to one of television’s most complex shows. The Good Place was a sitcom about moral philosophy, a phrase that remains absurd and seemingly impossible even after four masterful seasons. Mike Schur’s paean to the human capacity for improvement was equally adept at delivering fart jokes and arguing that the labyrinthine web of human suffering that is late stage capitalism makes it impossible to live a purely virtuous life no matter how hard you try. To say that The Good Place expanded beyond the bounds of what was supposed to be possible in sitcom television is to undersell it. This is a show that featured an avatar for every newsworthy Florida Man—a character who lovingly referred to his social space as a “bud hole”—and that also suggested that sentience was a failed experiment.

The Good Place was an incredible television show, is what I’m saying.

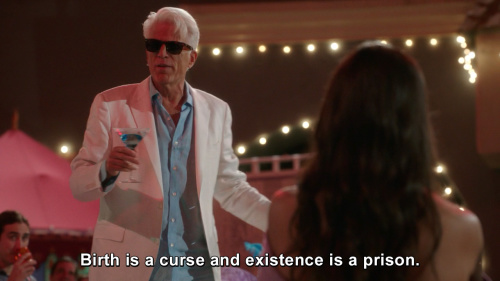

It was also home to one of the best twists in recent television history: Eleanor’s revelation at the conclusion of the show’s first season is iconic. The moment that she realizes she is not, as that green placard suggests, in the Good Place at all, and that she and her friends are actually in the Bad Place, being tortured by the demon that she thought was an angel, is a fantastic piece of writing. In that same scene, Ted Danson’s heel turn is, rightfully, the stuff of legend.

From that point, the show continued to invert its expectations. Eleanor, a self-described “trash bag from Arizona” becomes one of the most selfless beings in history; Jason, the aforementioned stereotypically insane Florida Man discovers the serenity of the monk that he long pretended to be; Michael, a literal demon (well, a fire squid), becomes an unfailingly compassionate human. But perhaps the greatest twist of The Good Place is that, even as the show struggled with massive stakes—saving humanity from eradication and, after that, completely redesigning the afterlife to save our very souls—those stakes are only meaningful because of the individual relationships of a handful of people. The world is saved and humanity is redeemed, yes, but the Arizona trash bag and the chronically indecisive professor found love, the Florida Man found wisdom, and the self-centered socialite found true charity.

The Good Place is an amazing piece of art. Fittingly, I honestly think the world would be a better place if everyone watched it. Because, in a final twist, the show’s big ideas aren’t that big in the end. Through their arcs, Eleanor and her friends showed that friendship, decency and compassion can save the world but that’s not what their journey was about. The true purpose of the show was much smaller and it involved six malformed people simply wondering what we owe one another and how to use that consideration to be better to the people around them.

Near the show’s end, Eleanor says that “there’s greater happiness waiting for you if you form bonds with other people” and in those words you can feel Schur stressing the thesis of this labor of love, a show that could have kept going except that it knew when it was time to go, that endings are an important part of being. In The Good Place big ideas mattered but they only mattered because of the virtuous cycle they formed with small connections. Be kind to your friends and generous to strangers and the Good Place won’t have ended at all.